Protein Binding Pockets: Structure, Dynamics and AI-Based Prediction

A deep dive into what binding pockets are, how they shape enzyme function, and how modern AI and structure prediction tools let us map them at scale.

Protein Binding Pockets: Structure, Dynamics and AI-Based Prediction

When we talk about enzymes or receptors, we often reduce them to a sequence of amino acids or to a single label like “kinase” or “hydrolase”. But most of the chemistry and recognition that matters for biology is local. It happens in small, three-dimensional regions of the protein surface where ligands actually bind. These regions are binding pockets.

Formally, a binding pocket (or binding site) is a region on a macromolecule that binds another molecule with specificity – for example a substrate, inhibitor, cofactor, peptide or nucleic acid segment. The geometry and chemical environment of the pocket largely determine what can bind, with what affinity, and what reaction will occur.

In this post, I’ll go through what we know about binding pockets from a structural and biophysical standpoint, how we detect and compare them computationally, and how modern AI and structure prediction methods are changing what we can do – with a particular eye on enzyme annotation in complex systems like the microbiome.

1. What is a binding pocket, structurally?

A protein sequence is one-dimensional, but in the cell it folds into a three-dimensional structure where side chains pack, hydrogen bonds form, and secondary-structure elements arrange into a compact object. The surface of that object is not smooth. It has protrusions, grooves and cavities.

Binding pockets are concave regions of that surface where a ligand can be stably accommodated. Several properties matter simultaneously:

- Shape and volume. Pockets can be deep and narrow, shallow and wide, or extended grooves. Their size and topology constrain the possible ligands.

- Physicochemical patterning. The distribution of polar, charged and hydrophobic residues, as well as hydrogen-bond donors/acceptors and aromatic rings, defines what interactions are possible.

- Local flexibility. Loops and side chains surrounding the pocket can move, opening or closing access or fine-tuning the fit.

Large-scale analyses of tens of thousands of known ligand-binding sites show that despite the diversity of proteins, the structural space of small-molecule pockets is surprisingly limited: many unrelated proteins reuse similar pocket shapes and chemistries to bind similar ligands. This is a key reason why pocket comparison can reveal functional similarity even when global sequence identity is low.

Coleman and Sharp systematically analysed protein surfaces and proposed ways to define and compare pockets based on geometry, highlighting that the main challenges are: delineating the pocket boundary, characterising its shape, and developing quantitative metrics to compare pockets across proteins.

2. Pockets are dynamic, not rigid holes

It is tempting to think of a pocket as a static cavity “waiting” for a ligand. In reality, pockets are often dynamic entities whose shape and accessibility change over time.

Stank and co-workers reviewed pocket dynamics and proposed several mechanistic classes: formation or disappearance of sub-pockets, breathing motions that expand or contract the pocket, opening and closing of channels or gates, and the emergence of allosteric pockets that influence other sites.

From a functional point of view, this means:

- A pocket that appears small in one crystal structure may adopt a larger, druggable conformation in another state or along a molecular dynamics trajectory.

- Allosteric ligands can bind at transient pockets that only exist in certain conformations, modulating activity without competing directly with the orthosteric substrate.

- Mutations that affect flexibility around the pocket can be as important as those that change direct contact residues.

For enzyme annotation, pocket dynamics are a reminder that any static snapshot – experimental or predicted – is only one member of an ensemble. Methods that ignore flexibility risk missing relevant binding sites or mis-estimating their properties.

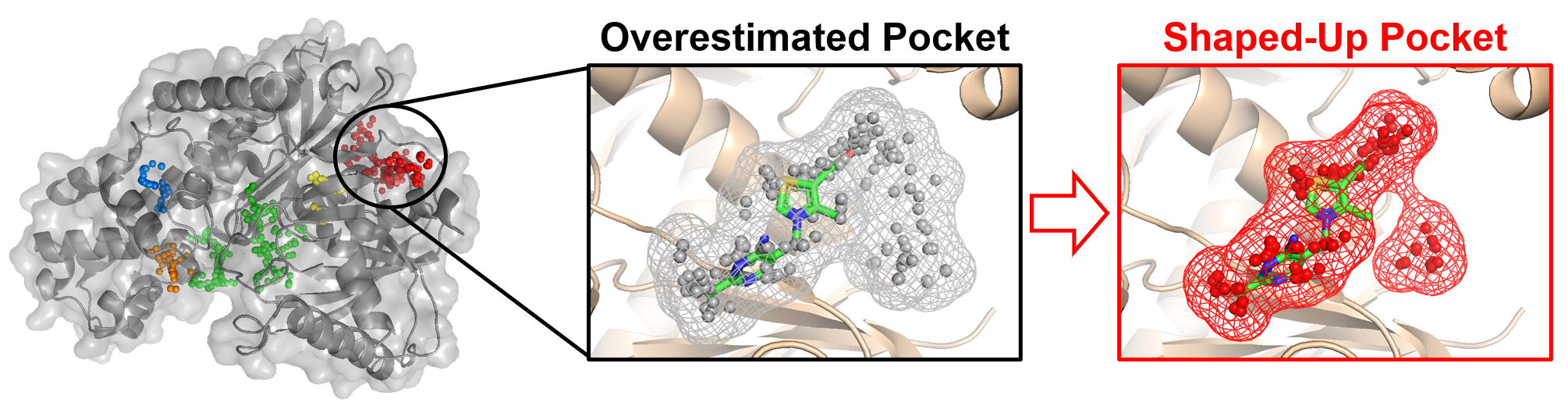

3. How do we detect binding pockets computationally?

Given a protein structure, the task “find the pockets” is conceptually simple but technically subtle. A variety of approaches exist, which can be grouped roughly into geometric, physicochemical/energy-based and knowledge-based methods.

Geometric algorithms focus on the shape of the protein surface. Tools like Fpocket use Voronoi tessellation and “alpha spheres” to identify regions on the surface where a small sphere can fit but solvent cannot, clustering these into candidate pockets. These methods are fast and well suited to large-scale screening of thousands of structures.

Energy-based methods sample probe particles or small fragments around the protein and evaluate interaction energies, marking regions where a ligand would be energetically favourable. These approaches can naturally incorporate electrostatics and hydrophobic effects, at the cost of higher computational expense.

Knowledge-based methods exploit the observation that unrelated binding sites can share local structural motifs that bind similar chemical fragments. By mining large datasets of known complexes, they build libraries of recurrent patterns and use them to identify and annotate pockets in new structures.

On top of these, there are now databases and surveys that treat pockets themselves as first-class objects. Gao and Skolnick described a comprehensive survey of ~20,000 small-molecule binding pockets from the Protein Data Bank, quantifying how often pockets recur, how promiscuous they are with respect to ligands, and how similar pockets can be used to infer function. Such work underpins many modern pocket-comparison algorithms.

4. The structure prediction revolution: pockets at proteome scale

All of the above assumed that you have a structure. Historically, this meant an experimentally solved structure, which was a severe bottleneck. The advent of AlphaFold2 and related deep-learning models has changed that landscape dramatically.

Jumper et al. demonstrated that AlphaFold can predict single-chain protein structures with accuracy competitive with experimental methods in many cases, including when no close template is available. Varadi and colleagues then released the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, providing hundreds of thousands of predicted structures for complete proteomes, with confidence metrics for each residue.

For binding pocket work, this has two major consequences:

- We can now run pocket-detection methods on entire proteomes or metagenome-assembled genomes, not just on the subset of proteins with experimental structures.

- We can integrate pocket features (geometry, composition, local confidence) into pipelines for function prediction and ligandability assessment at scale.

Recent developments like AlphaFold-style models that co-fold proteins with ligands or other biomolecules push this further, offering direct predictions of complexes, although they still require cautious interpretation and experimental validation.

5. Pocket-based function annotation and enzyme discovery

Why focus on pockets rather than entire proteins? Because function is often local and convergent.

Coleman and Sharp showed that defining and comparing pockets can reveal similarities that are not obvious from global structural alignment alone. Gao and Skolnick’s survey further found that both protein promiscuity (one pocket binding many ligands) and ligand promiscuity (one ligand fitting multiple pockets) are common. The implication is that pockets encode a rich, but non-trivial, mapping between structure and function.

In practical terms, a pocket-centric annotation workflow might look like this:

- Predict or obtain structures for a set of uncharacterised proteins (for example, from a microbiome dataset).

- Detect binding pockets and compute descriptors (shape, volume, hydrophobicity, key residues).

- Compare these pockets against a reference library of pockets with known ligands or reactions.

- Transfer functional hypotheses based on pocket similarity, even when sequence identity is low or the global fold differs.

Knowledge-based approaches that match local binding motifs rather than entire pockets also fall into this category and can, for example, identify nucleotide-binding or metal-binding sites in otherwise unannotated proteins.

In enzyme discovery, this is particularly powerful when combined with chemical context: if metabolomics suggests a certain class of reactions is occurring in a community, pocket-based searches can help prioritise which proteins are most likely to catalyse them.

6. Machine learning and deep learning for binding site prediction

Traditional methods use hand-crafted geometric or physicochemical features. In recent years, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have been increasingly applied to binding site prediction and pocket analysis.

Modern reviews highlight several trends:

- Sequence-based models that predict likely binding residues directly from multiple-sequence alignments and evolutionary profiles.

- Structure-based models that operate on 3D grids, point clouds or graphs derived from protein structures, often using convolutional or graph neural networks.

- Hybrid approaches that integrate sequence embeddings from protein language models with structural features.

Benchmark studies comparing dozens of methods across large datasets show that while classical tools like Fpocket remain strong baselines for pocket localisation, deep models can improve recall and precision, especially when scoring which pockets are biologically relevant in proteins with multiple cavities.

Importantly, many DL models now treat binding site prediction as a segmentation problem in 3D, labelling each surface patch or residue as part of a site or not, which aligns conceptually with the idea of pockets as spatial objects rather than global protein labels.

7. Why pockets matter for microbiome enzyme annotation

Metagenomic and metaproteomic studies routinely uncover vast numbers of proteins with no experimental characterisation. In microbiome research, especially in gut and mucosal environments, we care deeply about small-molecule chemistry: bile acids, short-chain fatty acids, tryptophan metabolites, xenobiotics and so on.

In that context, pockets offer a natural intermediate layer between sequence and metabolic phenotype:

- They help explain why enzymes with low sequence identity can catalyse similar reactions: the pocket architecture is conserved even when the rest of the protein diverges.

- They can distinguish between paralogs with similar scaffolds but different substrate specificities, based on subtle changes in pocket shape and microenvironment.

- They provide structural hypotheses that can be directly tested by mutagenesis or ligand-binding experiments.

AI-assisted pipelines for enzyme discovery in the gut microbiome increasingly make use of sequence embeddings, predicted structures, or both, to identify candidates involved in specific chemistries (for example, bile acid metabolism). Integrating pocket-based descriptors into these pipelines is a natural next step: rather than learning purely from global sequence, models can learn from local 3D environments where chemistry actually happens.

For microbial enzymes that act on host-derived molecules, this pocket-centric view is particularly attractive, because it ties together three levels of description: the microbial gene, the structural pocket and the measurable metabolite.

8. Caveats and open challenges

Despite the progress, several limitations remain:

- Quality of predicted structures. AlphaFold-like models provide confidence scores, but local errors around flexible loops can strongly affect pocket geometry. Not every predicted cavity is trustworthy.

- Dynamics and allostery. Most binding-site predictors operate on single conformations. Capturing transient or allosteric pockets still requires molecular dynamics or specialised methods, which are computationally more demanding.

- Biases in training data. ML/DL models are only as good as their training sets, which are heavily skewed toward well-studied, druggable targets. Their performance on microbiome proteins, membrane proteins or intrinsically disordered regions may be very different from benchmark datasets.

- Mapping pockets to function. Similar pockets do not always imply identical function; promiscuity and context matter. Integrating pocket information with genomic neighbourhoods, gene expression and metabolomics is essential for robust annotation.

From a practical perspective, the most reliable studies combine multiple lines of evidence: pocket prediction, sequence analysis, evolutionary conservation, docking, and where possible, experimental validation.

9. Take-home message

Binding pockets are the places where proteins “see” the world. They are small in spatial extent but disproportionately important for recognition, catalysis and regulation. Over the last decade, we have learned that the structural space of pockets is constrained and recurrent, that pockets are dynamic rather than rigid, and that we can detect and compare them computationally at scale.

The recent explosion of accurate structure prediction and the rise of ML/DL methods for binding site prediction now make it feasible to treat pockets as first-class citizens in enzyme annotation pipelines, including in complex ecosystems like the gut microbiome. The challenge – and opportunity – lies in combining this structural, pocket-level information with everything else we know about genes, pathways and metabolites, to build mechanistic stories that are both predictive and testable.

References

-

Coleman, R. G., & Sharp, K. A. (2010). Protein pockets: inventory, shape, and comparison. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 50(4), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci900397t

-

Gao, M., & Skolnick, J. (2013). A comprehensive survey of small-molecule binding pockets in proteins. PLoS Computational Biology, 9(10), e1003302. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003302

-

Stank, A., Kokh, D. B., Fuller, J. C., & Wade, R. C. (2016). Protein binding pocket dynamics. Accounts of Chemical Research, 49(5), 809–815. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00516

-

Le Guilloux, V., Schmidtke, P., & Tufféry, P. (2009). Fpocket: an open source platform for ligand pocket detection. BMC Bioinformatics, 10, 168. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-168

-

Bianchi, V., & Tiwari, S. (2012). Identification of binding pockets in protein structures using a knowledge-based method. BMC Bioinformatics, 13(Suppl 4), S17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-13-S4-S17

-

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596(7873), 583–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

-

Varadi, M., Anyango, S., Deshpande, M., et al. (2022). AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Research, 50(D1), D439–D444. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1061

-

Utgés, J. S., Beltrán, J. M., & De Fabritiis, G. (2024). Comparative evaluation of methods for the prediction of protein–ligand binding sites. Journal of Cheminformatics, 16, 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-024-00923-z

-

Vural, O., Cicek, A. E., & Sevim, V. (2025). Machine learning approaches for predicting protein–ligand binding sites from sequence data. Frontiers in Bioinformatics, 5, 1520382. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbinf.2025.1520382

-

Mou, M., Zhou, X., & Liu, R. (2025). Deep learning for predicting biomolecular binding sites of proteins, nucleic acids, and small molecules. Research, 2025, 0615. https://doi.org/10.34133/research.0615