Letting AI pick the right differential abundance method, taxon by taxon

Microbiome data are messy, and no single differential abundance method wins everywhere. Here I explore how AI could learn, taxon by taxon, which method is most reliable using modern benchmarks and simulated/semi-simulated datasets.

In microbiome analysis, differential abundance (DA) has become a kind of statistical Rorschach test. Give the same dataset to several popular methods—DESeq2, edgeR, ALDEx2, metagenomeSeq, LefSe, Wilcoxon-based approaches—and you will often get overlapping but substantially different sets of “significant” taxa. Large benchmarks have made that painfully clear: methods disagree a lot more than we’d like, and error control is often far from ideal (Nearing et al., 2022).

At the same time, we know that microbiome data are messy in very specific ways: they’re compositional, zero-inflated, overdispersed and often structured (longitudinal, repeated measures, multi-site). It is not surprising that no single method manages to be uniformly “best” across all these regimes. Weiss and colleagues showed years ago that normalization and DA performance depend strongly on data characteristics—library size, sparsity, effect size and more—and recommended tailoring the analysis to the properties of each study instead of applying one default pipeline everywhere (Weiss et al., 2017). More recent reviews reinforce the same message: the “right” DA method is inseparable from the structure of the data and the inferential target (Swift et al., 2023; Lin & Peddada, 2020).

Yet, in most real projects, we still apply one DA method (maybe two) to an entire abundance table and call it a day. Conceptually, that feels wrong. Each taxon lives in its own statistical regime: some are abundant and relatively well-behaved, others are extremely sparse, highly skewed or dominated by group-specific zeros. Treating them all with the same model is convenient, but it is also a very strong assumption.

My idea is to lean into that heterogeneity instead of smoothing it away: use AI as a meta-layer that learns which DA method tends to work best for a given taxon profile, and then apply methods in a taxon-specific way. Rather than asking “what is the best method overall?”, the question becomes “for this particular taxon, with these data characteristics, which method is likely to give the most reliable answer?”.

To make that more than a thought experiment, we have to take seriously the current state of benchmarking and simulation for microbiome DA, because that is where the training signal for such an AI system would come from.

What current benchmarks are really telling us

The last few years have seen an explosion of benchmarks for microbiome DA methods. Large comparative studies apply many methods to dozens of datasets—both real and synthetic—and then examine agreement, false discovery behaviour, sensitivity and robustness. Nearing et al. compared fourteen DA methods across thirty-eight 16S rRNA gene datasets and found dramatically different results across methods, even when applied to exactly the same data (Nearing et al., 2022). More recent benchmarks extend this idea to correlated or longitudinal designs, where repeated measures and structured variability make the problem even harder (e.g. Cappellato et al., 2022; Kohnert et al., 2025).

If there is one recurring message, it is that there is no universal winner. Some methods control the false discovery rate reasonably well but lose power in sparse settings; others are sensitive but optimistic, especially when compositional effects or zero inflation are not handled well. Reviews such as those by Swift et al. (2023) and Lin & Peddada (2020) summarize this landscape and emphasize that choosing a DA strategy is very context-dependent: normalization, modelling framework and even p-value aggregation all interact with data characteristics.

This is exactly the kind of problem where machine learning tends to shine: a large, messy space of configurations with no simple analytic rule that says which method will be best under which combination of sparsity, effect size, sample size and design. But before we can train a model to make such decisions, we need reliable labels. We need to know, for many different simulated and semi-simulated scenarios, which method actually performs best for each taxon and why.

From toy simulations to realistic synthetic microbiomes

Early benchmarks often relied on relatively simple simulation schemes: counts generated from negative binomial distributions with fixed dispersion, sometimes with a compositional constraint tacked on at the end. These approaches were useful, but they missed several defining features of real microbiome data, such as structured zero inflation, strong feature–feature correlations and complex relationships with covariates.

More recent work has produced simulation frameworks specifically designed to mimic microbiome data. SparseDOSSA2 is a good example: it models latent absolute abundances, sequencing depth, compositional effects, zero inflation and both feature–feature and feature–environment interactions in a hierarchical way (Ma et al., 2021). By fitting this model to real datasets and then simulating from the fitted model, researchers can generate synthetic communities that preserve the marginal distributions, sparsity and correlation structure of real microbiomes much more faithfully than simple negative binomial tricks.

Another widely used simulator is metaSPARSim, an R tool designed for 16S rRNA count data that explicitly aims to recreate compositionality and sparsity using a multivariate hypergeometric sampling step to mimic the sequencing process itself (Patuzzi et al., 2019). It has been adopted in several recent benchmarks comparing DA methods on synthetic data with controlled ground truth, often in combination with other simulators (Kohnert et al., 2025).

These tools represent a significant step forward: they allow us to systematically vary sample size, effect sizes, prevalence, correlation structure and confounders while staying reasonably close to the empirical distribution of real studies. But they still generate fully simulated worlds. The more assumptions we bake into the simulation model, the more we risk benchmarking methods on how well they match our simulator, rather than on how well they work on genuinely messy real-world data.

Semi-simulated data as a bridge to reality

To address that gap, there is a growing interest in semi-synthetic or semi-simulated approaches. Instead of generating an entirely artificial dataset from a parametric model, we start from a real abundance table and “inject” known signals in a controlled way—by spiking in differential shifts for a subset of taxa, by permuting labels, or by overlaying confounding structure on top of existing profiles.

Wirbel and colleagues recently proposed a realistic benchmark for DA and confounder adjustment in human microbiome studies, in which signals are implanted into real taxonomic profiles, including signals explicitly mimicking confounders (Wirbel et al., 2024). Their simulations aim to preserve the complex structure of genuine disease association datasets while still providing a known ground truth about which taxa truly differ between groups and which are only correlated via confounders. This is particularly important when evaluating methods that claim to handle confounding or compositional effects more gracefully: you want to see how they behave under scenarios that actually look like case–control or cohort studies.

Beyond individual studies, there is now an emerging literature explicitly focused on frameworks for semisynthetic simulation in microbiome analysis. Sankaran & Kodikara (2025), for instance, review how semi-simulated data can act as a “sandbox” for power analysis, method benchmarking and reliability assessment, emphasizing scenarios that look like real data while still providing ground truth. In parallel, packages such as benchdamic provide infrastructure to plug many DA methods, simulation engines and evaluation metrics into a single benchmarking pipeline, making it easier to explore a wide space of scenarios in a reproducible way (Calgaro et al., 2023).

Taken together, these developments mean that we now have reasonably mature tools to generate both simulated and semi-simulated microbiome data, across many different regimes, with labelled ground truth about which taxa are truly differential, which are null and which are affected by confounding.

That is exactly the kind of ecosystem we need if we want to go one step further and train an AI system that learns, taxon by taxon, which DA method tends to behave best.

Turning benchmarks into a training set for AI

The idea is conceptually simple, even if the implementation is not. In each simulated or semi-simulated scenario, we can compute a set of descriptive features for every taxon: prevalence, proportion of zeros, mean and variance by group, skewness and kurtosis, effect size, correlations with covariates, sample size and balance, and perhaps summary measures that describe the overall community structure of that dataset.

On the same scenarios, we apply a panel of DA methods—those already commonly used in benchmarks—and evaluate, for each taxon, how each method performs: whether it detects the true positives, whether it keeps false discoveries in check, how stable its p-values are across repeated simulations, and how it reacts to confounders. Benchmarks already do this at the level of whole methods or datasets; the twist here is to keep the granularity at the taxon level, rather than collapsing performance into a single method-level score per scenario.

For each taxon in each simulated world, we can then define a “winner” according to some criterion: for example, the method that maximizes sensitivity while controlling the false discovery rate below a threshold, or the method that optimizes a composite score combining power, calibration and stability. This choice is debatable and needs to be explored carefully, but conceptually it gives us a label: in this specific taxon-and-dataset context, method A performed best, method B was second, method C was disastrous.

Now imagine concatenating all these taxon-level examples across thousands of simulated and semi-simulated datasets generated with SparseDOSSA2, metaSPARSim and semisynthetic spiking frameworks. That becomes a large supervised learning problem: the input is a vector of taxon-level and dataset-level characteristics, and the output is the DA method that historically worked best under those conditions. A random forest, gradient boosting model or other flexible classifier could learn mappings such as “extreme sparsity plus strong group-specific zeros favours this type of zero-inflated model”, or “moderate prevalence, balanced design and strong compositional effects favour that compositional method”.

In this view, the current ecosystem of benchmarks and simulators becomes more than just a way to rank methods. It becomes a training generator for a meta-model that does not try to replace DA methods, but rather orchestrates them.

From thought experiment to practical workflow

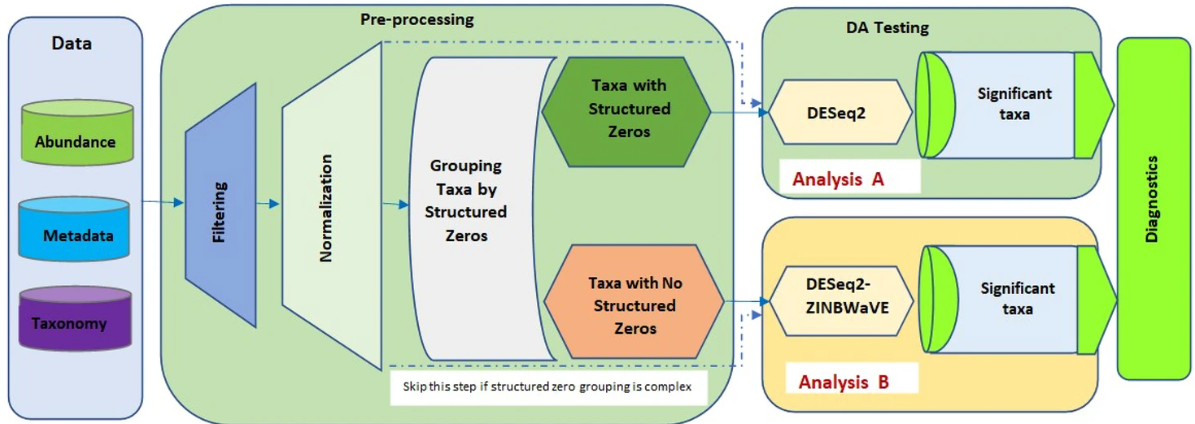

If such a model could be trained robustly—and that is a big “if”, requiring careful validation—it would change how we think about DA pipelines in practice. Instead of picking one method for the whole table, we would first characterize each taxon’s distribution and the overall study design, then let the trained AI model recommend a DA method per taxon, apply those methods accordingly and finally aggregate the results into a single output table.

This immediately raises the question of what happens to p-values and multiple testing when different taxa are analysed with different methods. Importantly, mixing methods does not automatically break procedures like Benjamini–Hochberg: they do not require all p-values to come from the same test, only that under the null they are valid (not anti-conservative) and not arranged in a worst-case dependence pattern. If, for each taxon, the choice of method is determined by a rule that depends only on label-invariant covariates—prevalence, proportion of zeros, dispersion, library size, study design—then the AI layer is essentially a fixed decision rule, and the resulting p-values can still be fed into standard FDR control. This is something we would need to confirm empirically in large simulations, but it is conceptually sound.

The real danger is adaptivity: if the recommender is allowed to look at quantities that change when you permute labels (observed fold-changes, preliminary p-values, etc.), then it can bias p-values downward under the null and quietly inflate the FDR. To avoid that, either the model must be restricted to label-invariant features, or we accept the computational cost of techniques like sample splitting or cross-fitting, where one subset of the data is used to choose the method and a disjoint subset is used for the actual test. In particularly demanding settings, one could even fall back on permutation-based calibration—using the AI-chosen method but deriving p-values empirically from label permutations—which is expensive but conceptually very clean.

All of this reinforces a key point: the success of a taxon-specific, AI-guided DA pipeline will depend not only on how well the model predicts “good” methods, but also on how carefully we design that model so that p-values remain trustworthy and FDR control is preserved in practice, not just on paper.

Why I think this direction is worth pursuing

In the end, my motivation is not to crown yet another DA method as the champion, but to acknowledge that the right tool depends on the taxon and the dataset, and that we finally have enough benchmarking and simulation infrastructure to let a machine learn those dependencies explicitly.

Benchmarks have already shown us that method choice matters a lot and that performance depends strongly on data characteristics. Simulators and semi-synthetic frameworks now give us a way to explore that dependency space in a systematic and realistic way. The natural next step, to me, is to treat all of this as a training ground for an AI system that can act as an informed recommender: for this taxon, in this study, with this distribution, this is probably the safest and most powerful DA approach.

It will not replace statistical thinking or careful study design—nothing does—but it might finally move us away from the “one-size-fits-all” mindset and toward an analysis culture that takes seriously the fact that each taxon lives in a different part of the statistical landscape.

References

-

Nearing, J. T., Douglas, G. M., Hayes, M. G., et al. (2022). Microbiome differential abundance methods produce different results across 38 datasets. Nature Communications, 13, 342. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28034-z

-

Weiss, S., Xu, Z. Z., Peddada, S., et al. (2017). Normalization and microbial differential abundance strategies depend upon data characteristics. Microbiome, 5, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0237-y

-

Swift, D., Cresswell, K., Johnson, R., et al. (2023). A review of normalization and differential abundance methods for microbiome counts data. WIREs Computational Statistics, 15(4), e1586. https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.1586

-

Lin, H., & Peddada, S. D. (2020). Analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, 6, 60. (And related review: “A review of normalization and differential abundance analysis in microbiome data”, npj Systems Biology and Applications, 6, 36.)

-

Ma, S., Shungin, D., Arzika, A. M., et al. (2021). A statistical model for describing and simulating microbial community profiles. PLOS Computational Biology, 17(3), e1008913. (SparseDOSSA2.) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008913

-

Patuzzi, I., Baruzzo, G., Losasso, C., Ricci, A., & Di Camillo, B. (2019). metaSPARSim: A 16S rRNA gene sequencing count data simulator. BMC Bioinformatics, 20, 416. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-019-2882-6

-

Wirbel, J., Essex, M., Forslund, S. K., & Zeller, G. (2024). A realistic benchmark for differential abundance testing and confounder adjustment in human microbiome studies. Genome Biology, 25, 247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-024-03390-9

-

Sankaran, K., & Kodikara, S. (2025). Semisynthetic simulation for microbiome data analysis. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 26(1), bbaf051. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbaf051

-

Calgaro, M., Romualdi, C., Waldron, L., Risso, D., & Vitulo, N. (2023). benchdamic: Benchmarking of differential abundance methods for microbiome data. Bioinformatics, 39(1), btac778. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac778

-

Cappellato, M., De Rubeis, V., Calgaro, M., et al. (2022). Investigating differential abundance methods in cross-sectional and longitudinal microbiome study designs. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 23(4), bbac243. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbac243

-

Kohnert, E., Patuzzi, I., Baruzzo, G., & Di Camillo, B. (2025). Benchmarking differential abundance tests for 16S rRNA microbiome data using metaSPARSim. PLOS ONE, 20(1), e0321452. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0321452

tance summaries that explain why the system tends to recommend a given method under certain conditions, echoing the “data characteristics” message from Weiss et al. (2017) and related work, but making it explicit and learnable rather than heuristic.