BEAUT: Using AI to Reveal Hidden Bile Acid Enzymes in the Gut Microbiome

A Cell paper introduces BEAUT, an AI pipeline that predicts over 600,000 bile-acid–modifying enzymes in the gut microbiome and uncovers a new bile acid that reshapes microbe–microbe interactions.

If you follow microbiome papers, you’ve probably seen some version of this sentence: “bile acids are not just detergents; they’re signalling molecules that shape host physiology and disease.” That’s true, but it hides a messy detail: once bile acids leave the liver and reach the gut, the microbiome starts to tinker with them in all sorts of ways. Microbes deconjugate, dehydroxylate, oxidise and otherwise remodel these molecules, creating a huge chemical zoo with very real consequences for metabolism, immunity and pathology.

We know these transformations are important, but we’ve had a surprisingly poor map of who in the microbiome does what. A few bile-salt hydrolases and classic enzymes are well characterised; the rest is a fog of “uncharacterised proteins” scattered across metagenomes. Connecting specific genes to specific bile-acid reactions at scale has been technically painful.

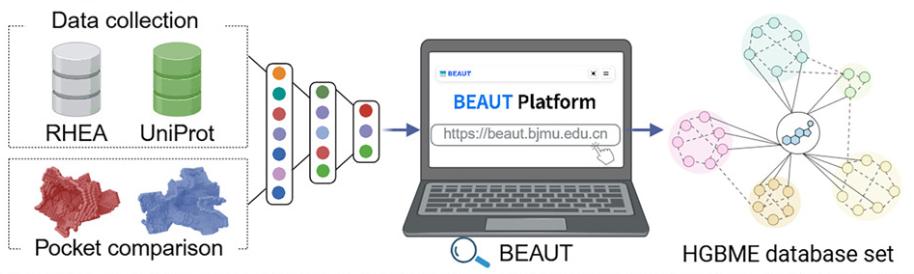

The Cell paper by Yong Ding and colleagues tackles exactly this problem with an AI-assisted workflow called BEAUT – short for Bile acid Enzyme Announcer Unit Tool.

The basic idea behind BEAUT

BEAUT starts from a simple question: given the protein sequences encoded by gut microbes, which ones are likely to be enzymes that modify bile acids?

Instead of manually chasing candidates one by one, the authors train an AI model on enzymes that are already known to act on bile acids, plus related proteins. The model learns patterns in sequence and structure that seem to go hand-in-hand with bile-acid chemistry. Then they unleash it on a massive collection of microbial proteins from the human gut.

The scale of the result is striking: more than 600,000 candidate bile-acid metabolic enzymes pop out of the pipeline. The team packages these into a public resource called HGBME (the Human Generalized microbial Bile acid Metabolic Enzyme database), accessible via the BEAUT website.

So instead of a handful of known enzymes and a sea of “hypothetical proteins”, we suddenly have a structured catalogue of possible bile-acid players that anyone can query.

From predictions to real biochemistry

Prediction is nice, but the convincing part of the paper is what they do next: they pick specific candidates and actually show what they do in the lab.

Among the newly characterised enzymes, two get most of the spotlight:

- MABH (monoacid acylated bile acid hydrolase), which cleaves certain acylated bile acids.

- ADS (3-acetoDCA synthetase), which does something much more radical.

ADS catalyses a reaction that extends the carbon skeleton of a bile acid, generating a previously undescribed molecule called 3-acetoDCA. This isn’t just a minor tweak; it produces a new “skeleton” bile acid via a carbon–carbon bond–forming step, which is unusual for this family of molecules.

The authors then track down the microbial origin of this chemistry, show how the enzyme works mechanistically, and confirm that 3-acetoDCA is not a lab artefact: it’s detectable in human stool samples across different populations and associates with the presence of the relevant microbial genes in metagenomic data.

A new bile acid that reshapes microbe–microbe interactions

Once 3-acetoDCA is on the table as a real metabolite, the obvious question is: what does it actually do?

Interestingly, the story here is less about direct signalling to host receptors and more about microbial ecology. At physiologically relevant concentrations, 3-acetoDCA influences how bacteria in the gut interact with one another. In the experimental systems the authors use, it alters the balance between species and modulates gut microbial interactions, rather than acting primarily through the classical bile-acid receptors in host tissues.

In other words, this new bile acid seems to work partly as a community-level modulator: a molecule made by microbes, acting first on other microbes, with downstream consequences for the host through changes in the overall microbiome and its metabolite profile.

Why this paper is exciting (beyond the shiny AI label)

A few things make BEAUT worth paying attention to:

First, it demonstrates a realistic workflow for using AI as a discovery engine in microbiome biochemistry. Instead of starting from individual genes and working upwards, the authors start from a biological function – bile-acid metabolism – and let the model scan huge sequence spaces to propose candidates, which they then validate experimentally.

Second, the HGBME database turns this from a one-off paper into an ongoing resource. If you work with metagenomes or MAGs, you can imagine overlaying BEAUT predictions onto your datasets to see which bile-acid enzymes are enriched in particular cohorts, disease states or interventions.

Third, the discovery of 3-acetoDCA is a reminder that we still don’t have a full catalogue of bile-acid chemistry in humans. Each new metabolite like this potentially adds another lever through which the microbiome can influence host physiology – sometimes directly, sometimes by reshaping the community itself.

One-sentence bar summary

If I had to compress the whole paper into something you could say over a beer, it would be:

“They trained an AI to hunt for bile-acid–modifying enzymes in the gut microbiome, predicted over 600k candidates, and then proved that at least one of them makes a completely new bile acid that can rearrange the gut microbial community.”

For microbiome people, BEAUT is both a dataset to mine and a template for how we might systematically uncover other hidden chemistries in our favourite microbial ecosystems.

References

-

Ding, Y., Luo, X., Guo, J., Xing, B., Lin, H., Ma, H., et al. (2025). Identification of gut microbial bile acid metabolic enzymes via an AI-assisted pipeline. Cell, 188(21), 6012–6027.e20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.07.017

-

Bile acid Enzyme Announcer Unit Tool (BEAUT) & HGBME database. (2025). Peking University. Available at: https://beaut.bjmu.edu.cn

-

Ding, Y., Luo, X., Guo, J., Xing, B., Lin, H., Ma, H., et al. (2025). Identification of gut microbial bile acid metabolic enzymes via an AI-assisted pipeline [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15388149

-

Winston, J. A., & Theriot, C. M. (2020). Diversification of host bile acids by members of the gut microbiota. Gut Microbes, 11(2), 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2019.1674124

-

Guzior, D. V., & Quinn, R. A. (2021). Review: microbial transformations of human bile acids. Microbiome, 9, 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-021-01101-1